The Coastside’s Southern Entrance

Story & Photos by John Vonderlin

Email John ([email protected])

Hi June,

My guess is that the first European set foot in what is now San Mateo County on October 20th, 1769. They almost surely did so on what most people call Bradley Beach. That first person was probably a scout for the Portola expedition, ranging ahead of the main expedition, which reached and made camp at the mouth of Waddell Creek on that day.

Below you’ll see excerpts from Miguel Costanso’s diary that describes that time and place.

Costanso’s Diary:

Friday, October 20.

As we set out from the camp a very long slope presented itself; this we had to ascend after crossing the stream which flowed at the foot of the hill to the north. It was necessary to open the way with the crowbar, and in this work we were employed the whole morning. We afterwards travelled a long distance along the backbone of a chain of broken hills, which sloped down to the sea. We halted on the same beach at the mouth of a very deep stream that flowed out from between very high hills of the mountain chain. This place, which was named the Arroyo or Cañada de la Salud, is one league, or a little more, from the Alto del Jamón. The coast, in this locality, runs northwest by north. The canyon was open towards the north-northeast, and extended inland for about a league in that direction.

From the beach a tongue of land could be seen at a short distance, west by north. It was low, and had rocks which were only a little above the surface of the water.

To the Cañada de la Salud, 1 league. From San Diego, 177 leagues.

(Picture #6402 at California Coastal Records Project [CCRP] showing the bluffs and the valley behind them shows why the weary explorers would have picked this wonderful spot to rest. The tongue of land he was referring to is Ano Nuevo Point)

Saturday, October 21.

We rested in this canyon while the scouts employed the day in examining the country.

Observed with the English octant, facing the sun, the meridian altitude of the lower limb of the sun was found to be … 41°41’30”

Astronomical refraction to be subtracted … 1′ Inclination of the visual [horizon] in consequence of the observer’s eye being three to four feet above sealevel, subtract … 2′

Semidiameter of the sun to be added … 16′ 13′

Altitude of the center of the sun … 41°54’30”

Zenith-distance … 48°5’30”

Its declination at that hour was … 11°2’3″

Latitude of the place … 37°3′

During the afternoon and night heavy showers fell, driven by a very strong south wind which caused a storm on the sea.

(You’ll note in Picture #6402 of Waddell Creek in the CCRP pictures that the latitude of this spot is actually 37 degrees 5.69 minutes. Still, to be so accurate with such primitive instruments is a testimonial to the skill of these explorers)

Sunday, October 22.

The day dawned overcast and gloomy; the men were wet and wearied from want of sleep, as they had no tents, and it was necessary to let them rest to-day. What excited our wonder on this occasion was that all the sick, for whom we greatly feared lest the wetting might prove exceedingly harmful, suddenly found their pains very much relieved. This was the reason for giving the canyon the name of La Salud.

(It is interesting to note in Father Crespi’s, Portola Expedition diary that he mentions this place was initially named the “Valley of San Luis Beltran,” and only after many of the sick recovered so quickly, despite a sleepless night in the cold rain of that late October day, was it renamed “Valley of Good Health.”

(Saint Beltran had been an early Dominican missionary in Colombia noted for his defense of the Indians against the more greedy and violent colonialists)

Here’s a picture of what that first scout, probing the beach to the north for the best path, would have seen.

The rock projecting into the ocean in the foreground is known as “Alligator Rock”. In the background we see Ano Nuevo Point and San Mateo County. On the right are the Waddell Bluffs.

“Alligator Rock,” so named because when the tide is in, it looks like a partly submerged alligator lurking watchfully for any unwary prey.

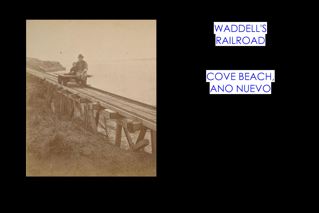

Waddell Bluffs is named for William Waddell, an early settler and lumberman from the nearby coastal mountains. He built a sawmill up Waddell Creek, in what is now Big Basin State Park. The cut timber was hauled in mule-drawn carts on wooden rails through the canyon to the coast for shipping. His plans for a wharf at the mouth of Waddell Creek were foiled by bedrock that made it impossible to drive piles for a wharf, so he extended a tiny rail line north to Cove Beach on Point Ano Nuevo.

From there he built a 700- foot long pier into deep water.

A swinging chute at the end loaded lumber onto awaiting schooners. Built in 1864, Waddell’s wharf was moving two million board feet of timber three years later.

After successfully conquering all the dangers of logging the mighty redwoods and shipping them off to market in rickety boats, Mr. Waddell was tragically mauled by a grizzly bear while deer hunting, soon after dying of complications in 1875.

The Bluffs themselves have left a longer lasting legacy. They, and their continual landslides, served as a natural barrier to transportation to the north, turning the routes that fostered major development inland to the Santa Clara Valley, leaving much of the Coastside undeveloped.

Even today, Highway 1 remains gripped in a perpetual battle with the ever-eroding talus slope of the Waddell Bluffs. Every year between 17,000 and 26,000 cubic yards of sliding material is removed, and then dumped onto the western side of the highway, keeping the road clear, and preventing it from falling into the sea, as the soil, and rock below it, are carried away by waves.

At the turn of the 20th century, road-builders were not so successful. Stagecoaches, carriages and wagons had to time their arrival to this stretch of beach at low tide. For about three quarters of a mile north of Waddell Creek, they would have to proceed over the recently wave-swept beach.

At the halfway point of this risky traversal, they reached what was known locally as “Cape Horn.” (Named after the tip of South America because of the extremely difficult, dangerous trip rounding the continent in the icy storm infested waters.) This was a continually sliding area just above Alligator Rock. There they had to temporarily leave the beach and climb a steep, rutted path across the landslide rubble from the Bluffs to get around a promontory. Fresh landslides stopped traffic north and south until the rubble was cleared.

In this century, to put your foot on the most southerly stretch of San Mateo County’s beaches you must climb down the large riprap boulders where “Cape Horn” was, just feet south of Alligator Rock. You can see it and the nearby parking spot in

Picture #6397 on the CCRP website.

Reaching the beach, head north, and after about two hundred yards, you’ll reach the Promised Land of Saint Matthew, for whom San Mateo County is named.

Continuing north you’ll soon come upon Wilson Falls, the most southerly waterfall in San Mateo County.

Not much further is the more picturesque Elliot Falls

As you are walking along, you might want to look around for the rocks that I call “eyeballs.” They are black chert nodules with layers of white material. Differential erosion often leaves them looking like eyeballs.

The local Ohlone Indians gathered the large, solid pieces of black, glassy chert, and used them for tool manufacturing, or for trading items with inland tribes.

Several times while walking this stretch, I’ve met geologists who told me this area is a good source of “agatized whale bone.” Not having the tools, time or desire to convert the dull rocks they showed me into polished specimens, they remain a mere curiosity.

As we head further north we come to a place where the beach narrows considerably, disappearing entirely at high tide.

Look up at the Cliffside, and you’ll notice a number of concretions, many spherical, a few dumbbell-shaped, partially eroded from the soft rock.

If the tide is favorable you can continue northward, and in a few hundred yards you’ll view Finney Falls, the only waterfall I know besides Pfeiffer Falls in Big Sur, that drops right into the surf at times.

Because it’s partly fed by irrigation on the coastal terrace above, Finney Falls can be flowing during anytime of the year, though winter is best. Watch for concretions, layers of fossils

or scattered individual ones in many places in the cliff. Be aware though that this whole stretch is very unstable, and it’s common to find a new cliff collapse whenever I visit.

Continuing northward you’ll reach New Year’s Creek. At this point climb the path that will take you across the old bridge and back to the free parking spot on Highway 1, or continue to the end of the beach where the most southerly arch in San Mateo County is located.

This is also near where the pictures of Waddell’s wharf and railroad were shot. Waddell’s warehouse and lumberyard stood Just above you on the blufftop.

Nearby there’s a path that heads up to the trail on the bluffs that heads northwest to the Elephant Seal rookeries on Ano Nuevo Point. Usually, after the 31st of March, the trail is open without the need for a docent guide. Or you can head back to the main parking lot and Ranger station. Enjoy. John Vonderlin