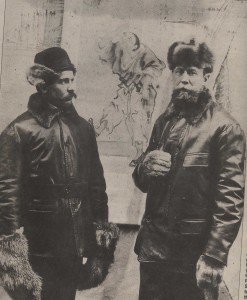

(Image: World renowned geologist Bailey Willis, at right, with topographer R. Harvey Sargent ready to embark on their historic China trip in 1903.)

(Image: World renowned geologist Bailey Willis, at right, with topographer R. Harvey Sargent ready to embark on their historic China trip in 1903.)

Professor Bailey Willis hunted earthquakes

By June Morrall

When the fearless 72-year-old Stanford geologist Bailey Willis went on an African safari in 1929, he wasn’t interested in wild animals. He was hunting earthquakes.

For years, the internationally known quake expert had studied traces of temblors all over the world, and in San Mateo County, he carefully tracked the San Andreas Fault from Mussel Rock southeast to Crystal Springs Reservoir and Searsville Lake.

No wonder he was called “Earthquake Willis” – although the eminent structural geologist, seismologist, explorer, world traveler, author, painter and lecturer would have preferred to shake off the nickname.

At age 65 in 1922, Willis retired from Stanford’s faculty, but he wasn’t the retiring kind. As professor emeritus, he remained as active as one of those smoldering volcanoes that fascinated him.

When he became president of the American Seismological Association, he helped produce an “Earthquake Map of California,” pinpointing the location “of the faults which traverse the rocky foundations of California, and may be the origin of earthquake shocks.” More importantly, the published map “was designed to show the lines on which earthquakes may occur and which, therefore, should be avoided by structures liable to damage by earthquakes.”

Willis cared a great deal about preventing the loss of life and property due to nature’s frightening disruption. Always self-assured and opinionated, he believed the devastating fires accompanying the 1906 San Francisco earthquake could have been prevented if the water mains had been properly protected from bursting.

“The fact that fire consumes cities after an earthquake is an indictment,” he once charged, “not an excuse.”

Many of California’s early building codes evolved from experiments Willis conducted on an “earthquake table” in a Stanford laboratory. The geologist simulated natural shocks while observing their effect on model building structures, composed of different materials. He experimented with novel ideas at his home on the campus, quake-proofing it with “pendulum and roller arrangements,” theorizing that in the event of a sharp jolt the building would roll or swing and not break.

On the lecture circuit, Willis shocked audiences when he discussed experimental methods of safeguarding buildings against earthquakes, including the radical concept of freeing structures from their foundations, putting them on ball bearings and equipping them with springs and shock absorbers. One day, he hoped, earthquakes could be scientifically predicted.

According to legend, Willis warned a Santa Barbara audience in the summer of 1925 that their city was in imminent danger of suffering a significant quake, when, lo and behold, his words became prophetic and the earth began to move. The 6.3 magnitude quake caused the deaths of 14 people and $6.5 million in damages. From that moment on, Willis was burdened with the nickname: “Earthquake Willis.”

Willis often said there was only one grain of truth in the story. He was in Santa Barbara during the quake jotting down observations while the bricks were still falling—but that was the extent of his involvement.

He concluded that earthquakes could not destroy a well-constructed building in California. Damage occurred only in the case of faulty design, a poor choice of building materials, or an ensuing fire.

Bailey Willis was born in Idlewild-on-Hudson, New York, in 1857, the son of Nathaniel Parker Willis, a poet and co-founder of “Town and Country,” the nation’s second-oldest magazine. Willis earned a mining and civil engineering degree at Columbia University and a Ph.D. from Germany’s University of Berlin.

In 1880 when he was in his early 20s, Willis was hired by the Northern Pacific Railway to search for coal deposits north of Mount Rainier in Washington state. The young geologist would never forget the magnificent wilderness territory.

As Willis and his crew cut a swath through the dense cedar forest in the upper Carbon River, he encountered stunning wildflower meadows today known as Spray Park. Nearby loomed Rainier’s “immense cavitated [???] face,” later named “Willis Wall” in his honor.

Mount Rainier’s majesty as a geological wonder had made its impact on Willis. After he joined the U.S. Geological Survey, he proposed to fellow geologists that they band together and work to have Mount Rainier preserved as a national park. From this tiny group of geologists the movement swelled, gathering support from other scientists and environmental groups including the Sierra Club in San Francisco.

In 1900 to the joy of all, President McKinley officially declared Mount Rainier a national park.

Widowed after 14 years of marriage, 41-year-old Willis wed Margaret (Margery) Delight Baker in 1898. The couple settled down to life in Washington, D.C., where their dining table attracted an interesting cast, a lively place dominated by intellectual conversation.

One special guest was R. Harvey Sargent, Margery’s cousin from Maine. Bailey liked the young man immediately, and helped Harvey connect with the USGS, kicking off his distinguished career as a topographer. The two men would collaborate on an important mission in the years to come.

Well known at the USGS for his structural analysis of the Appalachian Mountains, Willis’s career took a new direction in 1903. That year, the Carnegie Institution sent him and geologist Eliot Blackwelder on a geological-geographical expedition of the remote interior of China—a 2,000-mile, nine-month adventure on foot.

China’s winters were cold and the political climate edgy at the time. The Boxer Rebellion, marked by strong anti-foreign feeling, had barely ended and a war between Japan and Russia threatened. Margery Willis, who accompanied her husband on many future trips, was discouraged on this occasion. All agreed this one was too dangerous.

The historic expedition required an intrepid team willing to endure hardship and the dangers of an uncertain political atmosphere.

“To accomplish his mission properly, Bailey Willis needed to have a very good topographer, a mapmaker on his team, and he asked my grandfather to join him,” said Bob Sargent, grandson of R. Harvey Sargent.

While Willis traveled via Europe and across Siberia to Peking, China, he asked Harvey Sargent to be on “standby” for the call.

“My grandfather was in the fields in Utah working for the USGS when Bailey Willis’s call came,” said Bob Sargent, a former Foreign Service official with the Department of State, residing in Maine when I contacted him. “He traveled by train from Utah to Maine for a 24-hour visit with his family, then back across the country by train, and on to China by steamship.”

Willis and Sargent rendezvoused in Peking in December 1903, their meeting recorded in a photograph showing the famous geologist and the young topographer attired in leather winter jackets and fur mittens.

Some have wondered if Willis’s mission had political underpinnings.

“Competition among European countries, and the United States for influence in China during this period gives rise to speculation,” reflected Bob Sargent. “And certainly the Chinese were wary. But I have seen no evidence that economic, political or military intelligence may have been the objective of Bailey Willis’s mission.”

The team launched its expedition with great expectations, all fulfilled. The excellent, accurate maps produced by Harvey Sargent were the first of their kind, winning the expedition a gold medal from the Geographical Society of France.

Both Willis and Sargent carried camera equipment, and Bob Sargent inherited the collection of 150 images snapped by his mapmaker grandfather on the expedition. He also suggested that glass negatives taken by Willis exist somewhere and hopes that someday they will turn up.

Inspired by his grandfather’s photos, Bob Sargent organized a traveling exhibit called: China: Exploring the Interior (1903-4), providing a glimpse of rural China two years after the Boxer Rebellion.

The exhibit (to visit, click chinaexhibit.org) also includes his grandfather’s journal, and a map of the exhibition as well as the published findings. The show has traveled to colleges, libraries and historical societies back East, but in 2000, when I wrote this story, Bob Sargent wanted to see the images out west in “Bailey Willis country.”

(Image: In 1903, in China, a curious crowd watches Bailey Willis take a photograph of a “spirit screen,” erected to ward off evil spirits.)

(Image: In 1903, in China, a curious crowd watches Bailey Willis take a photograph of a “spirit screen,” erected to ward off evil spirits.)

A detailed, scientific report of the China trip appeared in the early 1900s, but Stanford University Press later published Willis’s more intimate account, “Friendly China,” including letters and drawings by the author. In the book, Willis dispelled apprehensions some had at the time about the team’s safety. These fears were groundless. He was confident the Chinese people would be friendly and they were.

Willis joined the Stanford faculty in 1915, becoming known as an international earthquake expert, traveling to wherever “shakes” were frequent.

With son, Robin, an oil geologist, he explored the California coastline from San Luis Obispo to Santa Rosa. He visited Japan, the East Indies, the Mediterranean, India and South America where he worked as a consulting geologist in Argentina.

But controversy was always around the corner.

In 1934, Willis questioned the stability of the foundation material upon which the south pier of the Golden Gate Bridge was being constructed. Voicing grave concerns, he advised that a committee, composed of “independent and unbiased specialists,” meet to investigate possible geological problems.

This program didn’t sit well with Willis’s nemesis, Andrew Lawson, the UC Berkeley structural geologist, the renowned authority who had compiled the official report after the 1906 earthquake and fire. Lawson’s prestige was staggering. He had named the San Andreas Fault, and believed the south pier of the Golden Gate Bridge was just fine.

Professor Lawson was livid when he responded to Willis’s concerns as “a fine example of a boogy-boo dragged in by the ears from the recesses of a vivid imagination to scare people. The astonishing thing about his present attack upon the stability of the Golden Gate Bridge is that he should have restrained himself so long.”

Lawson prevailed in this confrontation between giants. The Golden Gate Bridge was completed and remains safe – so far.

Bailey Willis lived a long, full life. After wife, Margaret died in 1941, white-whiskered Willis continued to reside on the Stanford campus where generations of students knew him as “Earthquake Willis.” He could be seen riding his bicycle and exercising with the kids until he was 90.

He suffered a nasty spill on his bike, curtailing his activities, and Bailey Willis died at age 91 in 1949.